Originally published in Flourishing March/April 2010.

First, consider these facts:*

- Just 18% of our oil imports come from the Persian Gulf.

- The US produces 74% of all the energy it consumes.

- Because only 26% of our energy is imported, only 4.7% of US primary energy comes from the Persian Gulf. (18 x .26 = 4.68)

- There are 173 net oil importers in the world. So, if the US quit buying oil on the world market, there would still be 172 net oil importers.

- Crude oil contains about 18,400 Btu’s per pound.

- Corn contains about 7,000 Btu’s per pound.

- Wind-generated electricity may cost more than twice as much to produce as much electricity from plants fired by natural gas, nuclear, or coal.

Now, what is the law of comparative advantage, and why does it matter?

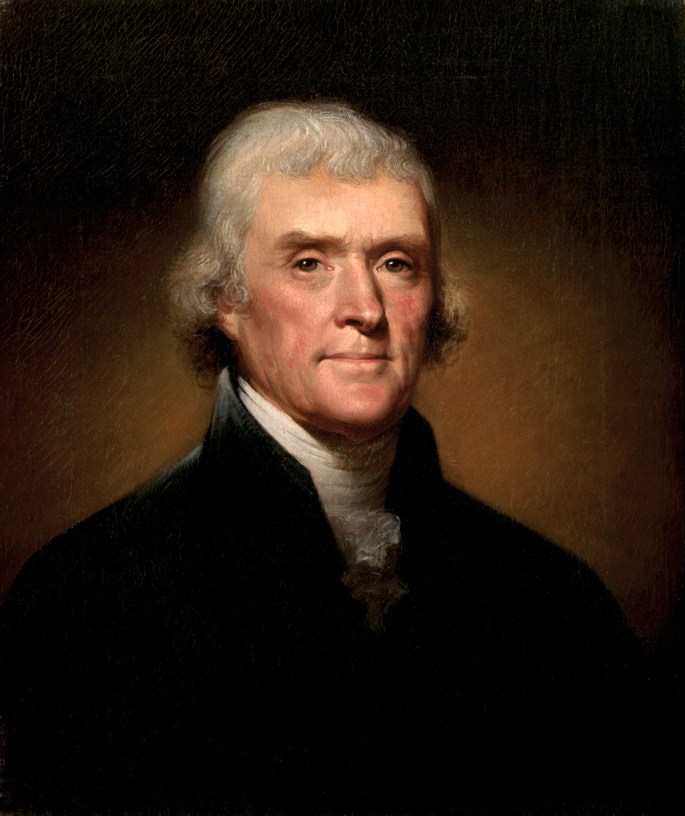

The law was first identified and formulated by the great British economist David Ricardo to explain that international trade and the division of labor are mutually advantageous to two or more countries, even if one is superior to the others in production of virtually any commodity, product, or service. In fact, the law applies to any situation involving the division of labor.

In his prime, Michael Jordan could play baseball better than 99% of all Americans. He did, in fact, earn a tidy sum of money playing minor league ball; but just about the same as others with similar ability. In basketball, though, Michael was the greatest player who ever lived. In basketball, the skill differential between Michael and the other players was much greater. As a result, Michael had more fun and made far more money playing basketball than baseball. Baseball was not hurt by Michael’s absence, and basketball was elevated immeasurably. That’s the law of comparative advantage.

The countries of the Persian Gulf are the Michael Jordan of oil—they have more oil than any other region of the globe. But, they don’t have much fresh water or arable land. In agriculture, they are, at best, minor league. For the sake of illustration, let’s assume that it costs those countries less than $10 per barrel to extract oil from the ground. Let’s also assume that producing corn, to whatever extent they might be able to do that, costs them at least $3.50 per bushel. If, based on world market prices, they can sell corn for $3.50 and oil for $75, their comparative advantage is clearly the production and distribution of oil.

What about us? Ignoring the fact that access to many of our own reserves is limited by the government, the United States itself has vast reserves of oil and other fossil fuels. The costs of bringing oil out of the ground in the U.S. vary widely, but let’s say the range is from $15 per barrel to $200 per barrel. With a market price of $75 per barrel, at what point does it make economic sense to import oil from the Persian Gulf countries? The obvious and correct answer is. . .

. . . anytime our cost of production exceeds the market price (in this case $75), we should purchase any additional oil we need—whether from Mexico, Canada, or any other country—in the world market for oil.

Producing oil domestically at a cost greater than that at which we can buy it overseas makes no sense. Nor do we benefit in the slightest degree from the attempt to attain energy independence via subsidized “alternative energy”. In either case, we simply increase our own energy costs. More importantly—like Michael playing baseball—we divert significant capital and human resources from industries where they could be employed more productively. In my opinion, growing corn for ethanol, instead of for food, is but one glaring example of such misallocation of resources. The “green jobs” boondoggle is another.

In sum, I believe it surely is true that we can and should produce a significant supply of energy right here in the U.S., but the law of comparative advantage tells us that the quest for energy independence is a fool’s errand. mh